C4 Pythagorean tuning system or myth of origin of Western music?

The following article was published in the 43rd edition of the periodical RIVISTA INTERNAZIONALE DI MUSICA SACRA, I-II, 2022, pp. 13-38, published by the Libreria Musicale Italiana. In addition, the didactic material of presentations XII and XXVII can be consulted.

What we call the Pythagorean tuning today was essentially summarized by Guido von Arezzo (* around 992-1050). By understanding what material the Benedictine monk had available and how he proceeded, we will try in the following to differentiate the Pythagorean part from the spirit of time of the turn of the millennium. The practical use of a monochord is definitely helpful for this.

Anyone who deals with the vibration behavior of homogeneous strings cannot ignore the partials - and especially the 2nd partial. Guido uses the term octave for this, which means so much that he imagines the distance to the prim divided into exactly 7 parts. In contrast, the ancient Greek expression diapason διαπασων means: through all notes.[1]As an alternative expression, Harmonia Ἁρμονία was also used, with which the special quality of consonance was expressed.[2] A specific numerical reference does not result from this, because, as Aristotle explains, the traditional tone designations were also used for the eighth tone level.[3] If Aristotle was induced to make such an explanation to his contemporaries, it means that the term Oktava οκτάβα was actually not in use. The Christian theological justification - the symbolic reference of the octave to the 8 Beatitudes of the Sermon on the Mount, which Guido mentions as a matter of course and rather en passant - must have been alien to Pythagoras.

What Guido comprehensibly describes is the insertion of the complementary intervals fifth and fourth, referring to the legend of Pythagoras in the forge.[4] This legend may be unrealistic in that beaten masses like hammers do not produce harmonies due to their weight. But regardless: The described interval ratios between octaves, fifths and fourths prove to be correct, as does the frequency ratio of the dissonant interval between two fourths and an octave of 9: 8. The legend does not provide any further material.

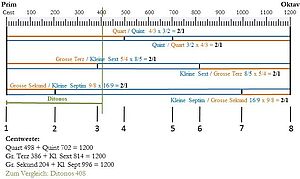

If we take Guido's account as given, it is worth noting that it is precisely the complementary intervals that are first of all found with the help of the monochord even without historical tradition. To a certain extent, the exploring ear cannot get past them. Guido, however, restricts himself to the fifth and fourth and leaves out the third-sixth ratio, which is just as easily identifiable as a complementary interval, which Archytas of Taranto (* 435-410 BC), for example, already used.[5]. The ratio of the major second to the minor seventh, however, results automatically from the further procedure.

It is very worth noting that in a construction intended for musical use, in which the consonance forms the basis in the sense of a beat-free fusion of notes, that important third-sixth ratios are disregarded. The 7 division of the octave would result naturally, but Pythagoras would not have to be used to determine this. Suffice it to say that the Greeks saw it that way. However, Guido is much more interested in referring to the legendary Pythagoras than on facts that can be directly ascertained. The difference between the complementary third-sixth ratio and the Pythagorean ditone can be seen in the following diagrams.

Complementary intervals (please click to enlarge)

All other constructive processes build on this basis, as if it were all about the preservation of tradition, but precisely because of the recognizable creative initiative, we must not attribute the process to unchecked ancient authorship - at least not specifically to the Pythagorean authorship.

The Pythagorean tuning

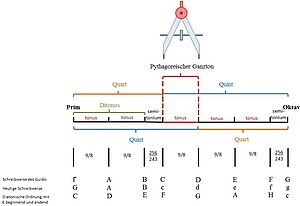

What Guido does is that he takes the difference between two fourths to the octave "in the circle" - in fact he knows the frequency ratio of the so-called Pythagorean whole tone of 9: 8 - and uses it as a module to start a Octave division into 7 sections.[6] Two such modules - which together form the ditonus, a Pythagorean major third - can be inserted without any problems, then a smaller part remains for the fourth, which we know as the Pythagorean semitone or leimma (remainder). It has a frequency ratio of 256: 243. He now repeats the same process from the fifth upwards. Again there is enough space for 2 modules and again the same residual value is added to the octave. The position of the semitone steps is due to this procedure. He gives the sequence the following names: Γ-A-B-C-D-E-F-G, using the same letter for the octave (here gamma and G) to express the consonance of the tones concerned. The so-called “master tones” emerged from this construction.

From the foregoing it becomes clear that Guido, figuratively speaking, reconstructs an entire building from the dimensions of a single Pythagorean building block. The construction goes back to himself first of all. In this respect, it would be appropriate to honor Guido von Arezzo as the author, even if he endeavored to put his own work in the shadow of the old master. From the cultural-historical context alone, which can only be sketched in the context of this study, the suspicion arises that the construction could serve the purpose of giving the theologically so eminently important term octave the necessary 7-level substructure and thereby creating the impression awaken that everything relates to ancient tradition. It makes sense to choose Pythagoras for this, since he was considered an authority even by the Church Fathers.[7]. Boethius writes: "If the teacher Pythagoras had said something, no one dared to ask for proof, since the teacher's reputation was proof enough." [8]The specific reason for the consideration is the surprising fact that an octave consists of 5 whole steps and two semitones and 5 whole steps and two half steps result in a mathematical reading of 6. Correct naming of the 2nd partial would have no influence on acoustic perception. Much later, we even encounter the addition of interval designations such as major second and minor third - literally: a major two and a minor three - which can only mean that the connection of the number eight with consonance was extremely important. Beyond the Bosphorus, things are different.

The time difference between Pythagoras (* around 570 BC - † 510 BC) and Guido von Arezzo (* around 992-1050) can be described as macro-historical at around 1500 years. On the other hand, Guido's information is surprisingly precise, while well-known music scholars who lived centuries earlier are only capable of vague statements - such as the transmission of the nebulous legend of Pythagoras' visit to the forge. Today, despite decades of music research, we couldn't say more about Pythagoras, and we don't even know with certainty whether he was familiar with the monochord, which Burkert doubts. He dates it to the time after Aristotle, since he had apparently not yet heard of it.[9]

Which other studies should Guido have known? Here, Aurelius Augustinus (* 354- † 430) should be mentioned in the first place, who in his six books on music gave the suggestion to subject the consonance to a different point of view by expressing that nothing is so similar to one another like the 1 to 1. For him it is an expression of total fusion and dearest love.[10]. No doubt he was thinking of the prim.

With Guido this view is already extended to the octave, as he writes: “Octave, whose peculiar nature is that it has the same letter on each side, as from C to c, and from D to d. Just as each of the two tones is denoted by the same letter, so both are held and viewed as having the same quality in every respect and the most perfect resemblance ”.[11] The relationship between the octave and the 8 beatitudes is already mentioned by Guido as given.[12] - with which prime and octave become congruent with the A and the Ω[13], the epitome of divine, all-encompassing presence.

The change in the way of looking at the 2nd partial tone - and thus the tremendous theological appreciation of the music that makes it specifically western and gives it a remarkable ethical content [14] - could therefore have occurred between Aurelius Augustine and Guido von Arezzo and does not allow any other octave division than that in 7 steps. By using the Pythagorean whole tone alone as a module, Guido gives the impression that he is merely presenting ancient ideas and that his own convictions have no influence. But he carries out the construction as such and cannot refer to anyone else except Boethius. It should be noted that the 5 books of Boethius contain a summary of Greek music theory and therefore gave him a certain overview.

If you take this into account, you read Guido's conclusion with different eyes: “In short! With the numerical ratios mentioned above, Pythagoras first constructed the monochord, on which, because it is not a frivolous gimmick, but a diligently given clear representation of this art, all scholars found their pleasure in the ordinary, and up to the present day art gradually increased and strengthened under the guidance of him who always illuminates the darkness of human knowledge, whose highest wisdom endures forever. Amen."[15]

Here he unexpectedly downgrades the Pythagorean achievement and emphasizes the development after him. Then he mentions the influence of the Most High and comes amazingly close to the actual state of the symbolic reference and the MUSICA DONUM DEI.

If we go in search of a possible point in time from when Christian symbolism assumed a decisive role in music theory, Boethius (* around 480 / 85- † 524/26) already provides a first indication, because he doesn't know the use of the same letter for the octave and progresses in the letter designation of the notes up to Z, to start again with AA to LL.[16] Accordingly, the highly significant theological reference was not yet known to him - even though Easter had already been given an octave day in its time, in which one could see a connection. Only after the pontificate of Gregory the Great is the introduction of octave days condensed. 615 Christmas also has an octave day, in the 7th century. then all the holy festivals.

On the other hand, Gregor von Nyssa (around 335- † 394) already encounters such a connection of the eight bliss with the Jacob's ladder - and even with the eighth note - so that it would certainly not have required a development of several centuries to make an analogy to the theory of harmony, especially the distinction between "high" and "low" tones was already used by Aristotle and Nichomachus.[17].

Gregor von Nyssa begins the introduction to the second speech with the words: “Whoever climbs up on a ladder rises, after stepping on the first rung, over it to the next higher, the second in turn leads him to the third, this one to the next one, this in turn to the one who comes after her, and so when climbing he gets to the highest step of the ladder by always rising from his point of view to the next higher rung. What do I intend to do with this input? I believe that the series of Beatitudes is laid out like the rungs of a ladder, and makes it easy for contemplation to ascend from step to step. Because whoever has entered the first stage of Beatitude in spirit, takes in the next with compelling necessity. "

And in the eighth homily with the title: “Eighth speech: Blessed are those who suffer persecution for the sake of righteousness” it says: “The order which the Lord has kept in his teaching full of wisdom and majesty leads us to the eighth level and with it to the superior saying; but it should be appropriate first to investigate which secret is contained in the octave which the prophet mentions in the title of two Psalms (Ps. 6 and 11 [Septuag. and Vulgate] [Heb. Ps. 6 a. 12]), and the importance of the commandment of purification and circumcision, which the law shifted to the eighth day. Perhaps this number has a relation to the eighth Beatitude, which, like the climax of all Beatitudes, occupies the last rung of the glorious spiritual ladder. There the prophet means with the symbol of the octave the day of the resurrection; […] From this point of view, the eighth Beatitude proclaims that entry into heaven is again open to people after they had fallen into bondage but have now been set free. […] See, this is the end of the struggles for God, the honorary prize for the effort, the victory reward for the sweat, that you will be considered worthy of the kingdom of heaven! Your longing for happiness no longer needs to focus on ephemeral and changeable things while wandering around. Because only the earth is the land of variability and change; But under everything that moves and shows in the sky you will not find anything that would be like this today and different tomorrow, but all heavenly bodies go their prescribed path in uninterrupted order and harmony. Do you still see the incomparable greatness of the gift that Beatitude offers you! Because her high reward does not consist in something changeable, so that then the fear of change could cloud the glorious hope, but her clear reference to the kingdom of heaven shows sufficiently that the gift of grace which she gives us hope is unchangeable and eternally constant.[18]

The immutability is precisely also the specific property of consonance, which Gregor von Nyssa does not yet mention, and with regard to the “secret in the octave” he does not find a solution. Seen in this way, the church has been waiting for the provision and preparation of the numerical and audio material for some time. This may have happened a long time before Guido, but we don't know anything about it.

If, for example, we learn from Eusebius of Caesarea (* approx. 260- † approx. 399) that Irenaeus is said to have written a work on the consideration of the figure eight, which is unfortunately lost[19], so wäre zumindest eine Erwähnung der Harmonielehre darin zu erwarten. Es hätte den Hinweis auf Nikomachos von Gerasa (*1.-†2.Jhdt.) enthalten können, demzufolge Pythagoras als erster der Lyra eine achte Saite hinzugefügt- und die Vollkommenheit der Oktav mathematisch aufgezeigt haben soll.[20]As mentioned, it should be noted that Nicomachus would not have used the numerical word, but it would have come to light through the translation of Irenaeus, as would the Christian context.

For liturgical reasons, the term octave was the first choice for the translation of the Greek diapason διαπασων. From the logic of counting tone steps, however, it does not result automatically. Euclid already demonstrated that the octave is smaller than 6 whole tones.[21]. Otherwise, as mentioned, an octave consists of 5 whole steps and two semitones. Both observations are beyond mathematical comprehensibility, since 5 whole and two halves result in 6. In addition, there is the importance of the prim, which the Greeks did not receive comparable appreciation as a consonant interval because, by definition, it was not an interval at all (cf. fn. 1).

The question arises, what the Romans numbered in order to arrive at the diapason with the number 8, if it could not have been intervals and tone steps. So we come back to the possibility that the tones were numbered in reverse order, i.e. that the consonance was first associated with the number 8 and then accepted having to count 2 semitone steps as a whole. In this context, it is also noteworthy that the descending Greek tone sequences have been transformed into ascending ones, because descending scales would literally not be useful from a Christian perspective. If the symbolism had an influence on the structure of our tone system at such an early stage, then not a single treatise from pre-Christian times should exist that already contains the Latin way of counting.Vitruvius [22] (1st century BC) and Plinius the Elder (* around 24- † 79)[23] used Greek interval designations and Aulus Gellius reports on Marcus Terentius Varro (* 116-27 BC) that he also used the Greek numerals, since Latin knows no expressions for them, literally: “Figurae quaedam numerorum, quas Graeci certis nominibus appellant, vocabula in lingua Latina non habent "[24]. Unfortunately, Latin non-Christian primary sources are completely absent. Direct access to Roman music is therefore closed to us. [25] All the more significant is the cited observation by Aulus Gellius.

The alternative variant would be that the counting only related to the number of tone levels, without considering the interval sizes, whereby the inclusive counting system was used. Inclusive counting was common at that time and we also encounter the terms diatesseron (through the four) and diapente (through the five) of the Greek tonal system.[26] It was therefore sufficient to complete the count accordingly. But these numbers would then also have been adopted for the intervals, although “intervallum” means “space”, and with 8 tones there are only 7 spaces. So there would be no space for an octave. Due to the fact that the interval definition of Aristoxenus (around * 360-ca. † 300 BC) does not allow a prim, this seems like an unnecessary addition, because up to then no one was ependent of the Prim. Assuming that something like this did not happen by chance, there would now be a valid reason. At the same time as the description of the intervals was translated into numerical values - because, remarkably, a translation of Diapason and Harmonia did not take place - the illogic mentioned above came to light.

No matter how things actually happened - this form of adoption into Latin corresponds to today's doctrinal opinion, without asking depending on the cause of the mathematical catastrophe. This is all the more astonishing given the fact that all those who dealt with the monochord took it in an exemplary manner from a mathematical point of view and exercised a teaching function. They critically examined definitions and created their own out of an interest in clear structures.

On the other hand, the mathematical deficit was compensated for by the theological-symbolic accuracy of fit. We see the analogy of sanctification on the first and eighth days and the covenant of God, which we will come back to later. Obviously it was time to renounce Greco-Roman polytheism and integrate the pagan clay material into the canon of creation. Why else, one might ask, was the translation into Latin not long before that, and why at all, when the Greek terms served their purpose for such a long period of time. In addition, it should be noted that both the Greek Oktava οκτάβα and the Roman Octav are well-known, almost identical numerals, which - at least from Aulus Gellius and from all those who have previously thought of a translation like - were not regarded as a perfectly fitting equivalent for Diapason διαπασων.

Günther Wille reports that Censorinus (3rd millennium) used the Latin expressions that had been created in the meantime.[27] According to this, the Christian attitude of mind could have already expressed itself before the Constantinian change, especially since the motives for the persecutors of the Christians were not easily recognizable.

We have thus reached the point where the consonances, as numerical new additions prim and octave, received their symbolic places of honor. If this was done for intentional reference, the period could be narrowed down. If not, a perfect structure was available that could be interpreted symbolically at any time and that would be just a fortunate circumstance from the perspective of the believers. For us this means that we have to start looking for the time of the symbolic appropriation of the sound system again. Before we do that, let's take another look at the symbol numbers as such:

Determinations and changes of liturgical processes, as they can certainly be made on the occasion of council resolutions and which can be observed more frequently in the early days, since the structures first had to take shape, inevitably lead to disruptions which in later centuries can no longer be understood. In order to create unambiguous relationships, evidence of other and earlier ways of thinking were usually destroyed, a fact about which image sources also provide information.[28] Therefore, there is a lack of documents that report how much these things were struggled with and which would subsequently be able to question the traditional perspective. This also undoubtedly includes traditions of pagan musical culture, because the denunciations of Roman cults as diabolical activities and demonic temptation are numerous and rhetorically powerful. Above all, Psedo-Cyprian branded lascivious dancing as well as the singing and strings of the Greek agone. Christian believers were forbidden to participate in such events.[29] It certainly played a role, at least in the early days, that the persecution of Christians by Diocletian and Galerius (303-311) was still traumatic in memory. Therefore, the tormentors' cultural assets will not have been treated with appreciation.

In general, with regard to the symbolism, it can be stated that in each individual case it is a matter of consensus. With the 5 wounds we are dealing with a consensus in such a way that either the two wounds on the feet of the crucified One are counted as one or the crown of thorns is not taken into account - we find both variants in artistic representations - because de facto it would be 6 (Crown of thorns, wound on the side, 2 hands, 2 feet). This is the only way to explain why we encounter five-wound crosses and five-wound rosaries.

The Seven Gifts of the Holy Spirit are a translation variant, which, however, must have met with acceptance, although the original Hebrew text in Isaiah only names six gifts. The two occurrences of the “fear of God” became once the “fear of God”, another time “piety”. It is obvious that adjustments have taken place here, especially since the various manifestations in liturgy, astronomy, music and geometry in the quadrivium were always viewed in correlation with one another. Among other things, it was about making the divine law and the divine order recognizable in all parts of creation. Double names like 6 wounds and 6 gifts of the Holy Spirit would only cause confusion - also because positive and negative connotations mix with one another. Since Augustine already speaks of 7 gifts of the Holy Spirit, we can assume that such fundamental determinations have already taken place before his time.

In the Sermon on the Mount, according to the account of the Evangelist Matthew, groups of people are named in nine consecutive sentences who deserve access to salvation because of their special virtues or because of their painful fate. 1. the poor in spirit, 2. the mourning, 3. the meek, 4. the hungry and thirst for justice, 5. the merciful, 6. the pure of heart, 7. the peaceful, 8. the persecuted - and In the 9th sentence it says: "Blessed are you [the disciples] when they revile and persecute you and tell lies all evil against you for my sake".[30] Es bedurfte eines Entscheides, um künftig nur von 8 Seligkeiten zu sprechen. Insbesondere deshalb, weil der letztgenannten Gruppe gleich im Anschluss eine besondere Ehrung zuteilwird: „Ihr seid das Salz der Erde.“ sowie „Ihr seid das Licht der Welt.“ [31] In addition, the Gospel of Luke is left out, which narrates the additional Beatitude: “Blessed are you who weep now, because you will laugh"[32and: "Blessed is he who does not offend me"[33]or the Gospel of John: "Blessed are those who do not see and yet believe"[34]

From the context it becomes clear that there must be a theological decision behind it, also in order to bring a certain order into the numerical material that enabled the believers to orient themselves mentally. One gets the impression that the early Christians saw the world anew with the Holy Scriptures. What later attained such eminent liturgical significance and left traces that were recognizable in numerous works of art as well as in customs across epochs, stood on earthy feet from the very beginning. At this point it was easy to set the course for the future. The creed took longer, as did the establishment of the Trinity.

In all of this, it should not be overlooked that historically backward-looking links to the Old Testament also made sense. The number eight was already connected with the divine before Jesus' lifetime, because circumcision was supposed to take place on the 8th day after birth and served for acceptance into the covenant of God.[35]. On the eighth day, a sin offering made atonement for uncleanness.[36]. There are also examples for the combination of the first and eighth day: “They began with the sanctification on the first day of the first month; and on the eighth day of the same month they came into the hall of the LORD, and they sanctified the house of the LORD eight days.“[37]Gregory of Nyssa already pointed out that two psalm verses begin with the hint to use the eighth string, which also includes the musical aspect. If, with the help of the psaltery or the harp, a parallel between consonance and divinity was drawn in the early days, we are lacking sufficiently informative sources for this. Apparently nobody remembered it. Samuels' report at least shows that David was able to improve Saul's state of mind with his zither game: "Saul felt easier, his condition improved and the evil spirit departed from him."[38] This can only be achieved with consonances.

If we continue to pursue the question of when we can count on a symbolic interpretation of the tone system and take as given the variant in which the prim and octave were already in place before Christian influence, then it was only necessary to refer to 8 of the 10 Beatitudes to establish a connection not only to the consonance, but also to the harmony of the spheres and the days of the week. With the Greeks and Romans, music was connected with the divine anyway, so Apollo was considered both the god of light and music. Seen in this way, the Christians adopted an existing worldview and were only interested in interpreting it in a monotheistic way. The same effect could have been achieved if one had only thought of the analogy to the covenant of God in the Old Testament with the commitment to the eight.

All of this shows that Guido von Arezzo had no reason to make any adjustments. His motivation was quite different: In his description, the omission of the complementary interval third-sixth was particularly noticeable. That would have meant that he would have relied on his own sensory perception and judgment. But that's exactly what he's not doing. We encounter a comparable attitude much later in Glarean (* 1488- † 1563), who dealt with the modes. He emphasizes. "So that the readers can see clearly that we are not inventing anything new, but that we have given back to its former glory what was almost buried for so long either through the negligence of people or through the unfavorable times."[39] Since his works were temporarily on the index[40] Glarean had every reason to be careful in his wording. He also informs us that his time would only recognize 8 - or rarely 13 - of the 14 modes, which consist of 7 octave genres.[41] Here the preference for known numbers becomes clear and also that the church had no interest in taking up individual interpretations, since it would have been detrimental to the credibility.

But Guido lacks such clues. In his case, however, the introduction of the Pythagorean mood has a correspondence in legends of origin and aitiological myths of origin - how many ruling houses traced their list of ancestors back to antiquity! - although he does not necessarily have to have made unauthorized changes. It is sufficient to refer back to the beginnings, which were in the dark and are now suddenly presented in bright light. It is significant that he refers to that of all people, to Pythagoras, who is considered the founder of the mathematical analysis of music even by the Greeks - the grip on the superlative cannot be overlooked. But Pythagoras will not have known an ascending scale, as Guido depicts it, with whole-tone steps lined up from the prim, ascending and ascending alphabetical naming of the tones. Guido had no other point of reference than Boethius.

As we have seen, Boethius was not familiar with the use of the same letter for the octave. Gregory of Nyssa was unable to fathom the secret in the octave, Aurelius Augustinus does not mention the octave relation to the prime, neither Isidore of Seville (* 560- † 636). In the overall view, it is inconceivable that all of the named would have left the analogy between the A and Ω with the prime and octave unmentioned if this important symbolic connection had already been established in their time. We are already in the time after Gregory the Great, (* 540- † 604) to whom the Gregorian chant at least owe its name.

The similarity of the octaved notes, which only reveals the special appreciation of the consonance, is an indispensable prerequisite for the analogy to the beginning and the end, and at the same time it is the basis for circular representations of later times, where we encounter the C at the zenith of the circle of fifths. In the nadir, on the other hand, the tritone appears, which Andreas Werkmeister called "Diabolus in Musica".[43]

Mention should be made at this point of the appearance of the tracery rose, which we encounter both in cathedral construction and as an ornament to the soundboard opening of musical instruments.[44] The position of the observer is noteworthy in this context, because while the tracery roses are only perceived in all their beauty from inside the church due to the light falling in, the sound passes through them to the outside and presents the instrument body as a sacred space.[45] Therefore, cross representations with the symbols of the evangelists can be found to decorate the soundboard openings.[46] as well as representations of the Trinity, surrounded by the eight bliss.[47] The bridge shape of the world's oldest clavizitherium in the form of the Jesse root indicates that the music comes from the House of David.[48]The inscription on numerous organs with the words: MUSICA DONUM DEI points in the same direction.

Perhaps Guido was aware that Pippin III (* 714- † 768), the father of Charlemagne, had connections to Byzantium - as a gift from the ambassadors he was given a water organ (hydraulis) - and that the Eastern liturgical chants in the so-called Octoechos were grouped together. Especially with the octoecho, however, the Byzantine 8-note system is meant with its own, far-reaching history and the influences were so powerful that we speak of a Carolingian renaissance [49]. The son of Charlemagne, Emperor Ludwig the Pious, had an organ made for his Palatinate in Aachen in 826 by a priest named Georg from Venice. [50] Organs present consonances and dissonances with particular forcefulness. This opens up a new perspective with regard to the issue dealt with here, but the time was ripe for the integration of consonance into the Christian worldview and so there was no need for external stimulation.

The term octave was given a macro-historical location by Guido von Arezzo, as if everything had always been set up in such a way, and with the choice of the St. John hymn of Paul the deacon [51] he praises that - John the Baptist - who pointed to the coming of Christ, which since then take over the solmization syllables that strive up to the octave. The longing for redemption can be heard acoustically, especially in the leading tone.

Of course, the consonance was present centuries before, regardless of the interval designation. [52] In the Gregorian chants this is the main theme - the acoustically audible connection to God. Against this background, it is not surprising that the occurrence of the number 8 in liturgical chants can be perceived particularly intensely. As Giacomo Baroffio notes: "Le strutture melodiche (modali) sono ben più di otto, ma otto è un numero particolare, con un fascino che nella visione simbolica del mondo sconfina nel magico. Il fatto che l'otto sia divenuto determinante anche in altri campi della vita cristiana - si pensi ai battisteri ottagonali - non rimedia per nulla il disastro della dottrina modale.”[53]

Also, as Baroffio notes, the mentioned symbol references were well developed in other areas: The octagonal shape of the baptismal font expresses that only with baptism was the possibility of attaining bliss. [54] In analogy to this, representations of the fountain of life can be seen.[55]The octagonal shape of the imperial crown shows that rulers, by the grace of God, were closer to salvation. Charlemagne with the Palatine Chapel and the Staufer Emperor Friedrich II with Castel del Monte have clearly expressed this claim with their octagonal buildings. Ultimately, the coronation was accomplished by none other than God's representative on earth. The idea of what that meant at that time has been lost in our time, as has the idea of the cohesion of the Christian worldview, of which Guido gives us an impression:

For example, he explains to us the connection between the tones and the days of the week, which begun with the Dies Dominicus began, by writing: "As well as we start over again after seven days, so that we always use for the first and the eighth day the same name, we also designate and name the first and eighth notes always with the same letter, because we feel that they coincide in a natural harmony in one note, such as D and d. "

The eighth day experienced a strong increase in importance due to the fact that the resurrection took place on this weekday, because the Bible explicitly says: "on the eighth day after the 7th, the Sabbath."[56]

In connection with the days of the week, which the Romans assigned to the then visible wandering stars - to which dies dominicus corresponded, for example, to dies solis - we arrive at the cosmic dimension, whereby those heavenly bodies were located in 8 spheres, above which the empire was God's spreading, an idea that we will find later in numerous book illustrations, for example with Nicole Oresme.[57]

In addition, Guido draws our attention to the occurrence of the number 8 in the 8 parts of the speech [58], as it says in the prologue of the Gospel of John 1,1: "In the beginning was the word and the word was with God Beginning with God." We learn from this: closeness to God must be associated with the number 8 around the year 1000. On the 8th day after Easter, Christmas and Pentecost, the octave day was celebrated in his time. In this respect, even the lying eight (∞) used as a symbol of infinity, introduced by the mathematician and royal chaplain John Wallis (* 1616- † 1703), can still be traced back to the widespread reference to symbols.

Against the background presented, it should certainly be considered whether the similarity of the octaved tones could not be traced back to Guido himself. This would be supported by the fact that he provides detailed reasons for this twice and does not simply assume the phenomenon to be known. Since he had made a name for himself in musical notation as a practical man and introduced the solmization syllables for didactic purposes - the Guidonic hand is also a very helpful invention in this regard - he would certainly be able to take such a practical step and once again underline the peculiarity that it contains insists that he did not consistently pursue the phenomenon of complementary intervals. A note from his hand, however, lets us refrain from this thesis: The second chapter deals with the notes and their number. There he explicitly writes: “in primis pronatur Γgraecum a modernis adjunctum.” [59] And this gamma, which was recently added, has an octave equivalent in G. Unfortunately, Guido does not give a source.

Here it must be taken into account that we are only looking into a time window, because the equivalence of the octaved notes was by no means foreign to the Greeks [60], only Boethius and Guido knew nothing about it. Apart from a direct transfer of content, we have to assume that there is a difference in the level of knowledge. Therefore we come back to the so-called Carolingian Renaissance. It makes plausible why a new Greek letter is being introduced because it was only new to Guido. Richter [61] reports on the addition of an additional tone Γ to expand it downwards and refers to the treatise on the pseudo-Odo Dialogus de musica, which is said to have been of great influence on Guido's work.

Due to the historical anchoring and the fact that the octaved tones are made famous by Guido, the amalgamation of music with the Catholic worldview is perfect. The capitals of Cluny Abbey, dating from around 1050, bear testimony to the fact that the eight church tones were treated with the utmost respect, because each one is shown in the insignum of a mandorla, which was usually reserved for the Majestas Domini. [62] If one visualises the relation of the prim to the alpha and that of the octave to the omega, nothing has changed in that regard. The eighth tone bears the inscription:

OCTAVUS SANCTOS OMNES DOCET ESSE BEATOS

Of course, this does not mean the individual “happy making” tone, but the described merging with the Most High, the goal achieved. The consonance is just as reminiscent of the existence of God as the light of the risen One due to his own formulation: “I am the light of the world. Whoever follows me will never walk in the darkness, but will have the light of life.”[63] Music could not be valued more highly. Günther Wille sees a clear relationship to the psalmody in the capitals of Cluny, also because the columns were at the place of the psalmody, i.e. in the choir. According to his point of view, they do not indicate a store of eight individual tones, but rather the eight psalm tone models and the tone system of the octo echo, [64] which, incidentally, can also come up with myths of origin. The four echoi kyrioi are said to be due to King David, the four echoi plagioi and the two echoi mesoi to King Solomon. [65] The time calculation from the birth of Christ rounds off the worldview. Christ is the structuring principle in all things.

Christian symbolism is therefore not to be understood as aesthetic decoration or as a relic of magical ideas of a Middle Ages that was described as dark. In keeping with the spirit of the times, it is the structural expression of applicable law. The laws come from God. “But you have arranged everything according to measure, number and weight”, it says in wisdom 11:21. The text of the law - not just the 10 commandments but all of the Holy Scriptures - is holy. Accordingly, the law - in gross disregard of the theory of harmony - was enforced and defended with the most cruel means and the index was still the most harmless way of getting rid of those ideas that would have been able to question the Catholic (all-encompassing) worldview put. The different ways of looking at things then and now are comparable to symbolism and heraldry. In our time one hardly perceives more than a historically referring decoration, at that time it was an expression of concrete legal claim and a demonstration of hierarchical position.

The Enlightenment displaced any form of symbolic reference - the introduction of the revolutionary calendar and the 10-day week may serve as examples - and took the Guidonian myth of origin as an opportunity to completely free music from its theological clutches. As described, this is historically not tenable, because the micrologus guidonis de disciplina artis musicae contains more of the spirit of the millennium than of antiquity.

From a secular point of view, the beautiful fabric of symbolic reference tears, because on the one hand only a highly idiosyncratic and mathematically ignorant translation from Greek leads to the consonance of the prime and thus to that interval that isn't one [66], while we have do it on the other hand with dogmatic decisions - here above all with the restriction to eight Beatitudes - without which a general bond with the Holy Scriptures and thus the draft of the Catholic worldview would be unthinkable. Of course, the relevant educational horizon was always the relevant framework.

However, regardless of the rational view, symbolism has a spiritually and psychologically significant component. For this reason, devotional candles are not lit for the purpose of illuminating the room. Numbers result in a structure of relationships that calls to mind specific biblical passages. Nikolaus von Kues informs about their conscious use: "If we cannot approach the divine in any other way than through symbols, then we will use the mathematical symbols most appropriately, because they have indestructible certainty."[67] Such certainty can be achieved the longing of believing people, because only certainty erases doubt. Hence there is reason to treat the testimonies of piety with respect, even if they do not seem rationally comprehensible. With all its symbolic content, music has the advantage of not being exposed to the expectation of having to prove something. Their presence is sufficient. As immaterial art, it has always played a mediating role in the divine, which we encounter in many cultures. Therefore, with a view to the West, it is not this reference that is the peculiarity, but rather the circumstances that were able to displace it - so thoroughly even that even the Pontificio Consiglio della Cultura rejected the musical symbol references presented as “teorie scientifiche”.[68] The reasons for this are inextricably linked with the terms Copernican Revolution and Enlightenment.

The liberation from the “regime” of octaved tone spaces shows - the expression used by Ivan Wyschnegradsky, one of the pioneers of microtonal music [69] - that the art of music is much richer than the Guidonic myth of origin allows. In return, medieval sacred music shows greater spiritual depth, devotion and beauty - and a more intimate connection to the other arts - than even Guido reveals.[70] The Augustinian basic principle: equality and similarity is a reliable guide to understanding European culture.

In the context of the Enlightenment, the desire for liberation also led to an idea of an autonomy of the arts, with reference to Immanuel Kant, especially to his criticism of the power of judgment of 1790. However, the subject at hand is not about a question at all the aesthetic judgment but the creed of very many people. In addition, the separation of the specialist areas should rather be viewed as a general side effect of the Enlightenment. It has to do with professionalization. The fear of “instrumentalization” is inappropriate in the arts, as they are created to follow the creative will of a composer or artist. The arts themselves do not judge their creators. What is special about the sound system is that the artistic means of expression, i.e. the available sound material, has already been instrumentalized. Basically, it is hardly any different in the optical arts, because what would architecture, painting and sculpture be without the light of day? In the time of Guido there were no individual artistic personalities, only executive tools in the hands of God.

The academic separation of departments is one thing; the separation of church and state is another. This separation is alien to the music. In it, as in cultural history in general, different things flow together and historical research endeavors to pay special attention to the diversity of currents and the balance of representation. The Hellenistic part of music and music theory does not suffer in any way if we also take into account the Egyptian, Jewish, Byzantine, Christian, Coptic [71] and Moorish parts.

The exclusion of the Christian reference to symbols and the ethical content of the occidental theory of harmony in school lessons is a contemporary phenomenon that is completely incompatible with academic principles. Symbol phobia is detrimental to the understanding of Western culture, which is all the more regrettable as the theory of harmony in particular has non-denominational and unifying qualities. It forms the only opposite pole to the globally widespread strategic way of thinking with its historically sufficiently documented collateral damage. In its ethical core, it is not about the art of music at all, but about the harmonious coexistence of people, their synergy, the modus vivendi in pace. [72] The decisive word in this context is love of one's enemies - according to the Christian view the basis and prerequisite for wisdom and bliss.

© 2021 Aurelius Belz

------------------------------------------------------

[1] The translation from Greek into Latin has its particular pitfalls. Thus, according to the definition of Aristoxenus, the prime is not an interval at all, since he defines: "Interval is that which is limited by two tones that do not have the same pitch", see Busch, Logos syntheseos, 53. Since the zero only Was introduced in Western Europe by Leonardo Fibonacchi in 1202, to a certain extent no other numerical value was available. Another difference is the peculiarity that the Greek tone series were viewed in descending direction, which is indicated by the fact that the musical notes taken from the alphabet were placed in the order from height to depth, cf.Nubecker, Ancient Greek Music, 96 In addition, it is noteworthy that the Greek names for pitches do not require a continuous numerical reference: Néte - (Νήτη) "the lowest", Paranéte - (παρανήτη) "the next to the lowest", Trite - (τρίτη) "the third", Mése - (Μέση) "the middle one ", Paramése (Παραμέση) -" those next to the middle one ", Lichanós - (Λιχανός)" the index finger ", Hypáte - (Ὑπάτη)" the top one ", Parhypáte - (Παρυπάτη)" the one next to the top one ". Thus it was quite possible to appreciate the phenomenon of consonance without explicitly associating it with a number. This, however, is an indispensable prerequisite for the symbolic reference to the Holy Scriptures and results to a certain extent automatically from the translation into Latin, since the Latin interval designations correspond to a consecutive numbering.

[2] Neubecker, Altgriechische Musik, 107

[3] Aristoteles, De problemata physica, XIX

[4] He writes explicitly in Chapter XX, 18, after he reports on Pythagoras: "The inquisitive researcher will find all this in the figures given above."

[5] Claudius Ptolemäus reports on it, see Petersen, Naturwissenschaften, 257

[6] The present illustration is based on a reconstruction of the work sequence that results from Guido's description. He, on the other hand, lined up the tonal material according to size and thus came more en passant to the octave and even went beyond it.

[7] Quacquarelli, L’Ogdogade Patristica, 31 particularly pointed this out.

[8] Boethius, book 1, XXXIII.

[9] Burkert, Weisheit und Wissenschaft, 353f.

[10] Augustinus, De musica VI, Kapitel XIII

[11] Guido von Arezzo, Micrologus, Kapitel V, 5

[12] Guido von Arezzo, Micrologus, Kapitel XIII, 2

[13] The author first referred to the Christian reference to symbols of occidental harmony in Sacrale Handys, Hägglingen, 2013 and in RIMS, 36, 2015, 49-79

[14] We are talking here in particular of the 7 gifts of the Holy Spirit, which, according to the Augustinian view, represent the 7 steps on the way to God. These are: fear of God, piety, love of neighbor, bravery, mercy, love of enemies and wisdom. For Ambrose, too, the 7 strings of the kithara symbolize the sevenfold grace of the Holy Spirit, see Wille, Musica Romana, 402. In this way, the Jacob's scale has an analogue in the scales, very different from the ancient Greek music theory, since these only knows descending pitches. Only later theorists describe the systems and ladders in an ascending direction, see Neubecker, Altgriechische Musik, 102

[15] Neubecker, Altgriechische Musik, 20

[16] Boethius; book IV, X, WILLE, Musica Romana, 689, drew attention to this.

[17] Levin,The manual of harmonics, 43

[18] Gregor von Nyssa, Acht Homilien; IIX

[19] Quacquarelli, L’Ogdogade, 27

[20] Levin, The manual of harmonics, 73

[21] Busch, Logos, 151

[22] Vitruv, 1981, 34

[23] Wille, Musica Romana, 441

[24] quoted according to Wille, Musica Romana, 417

[25] quoted according to Wille, Musica Romana, 16

[26] An example of the inclusive count from the Holy Scriptures is the day of the resurrection, as it is said, "risen on the third day". However, Mary Magdalene found the empty tomb on the eighth day of the week, explicitly on the day after the Sabbath. This means that from Friday to Dies Dominicus was counted 3 days. The two statements do not contradict each other, which Isolde Meinhard apparently assumes, see Heinz, Kleine Kulturgeschichte der Achtzahl, 93.

[27] Wille, Musica Romana, 417

[28] e.g .: The burning of Arian books by Emperor Constantine, MS CLXV, um 825, Biblioteca Capitolare, Vercelli

[29] WILLE, Musica Romana, 388, dedicates a separate chapter to the Christian discussion of pagan music

[30] Mt. 3-12

[31] Mt. 5,13f

[32] Lk. 6,21

[33] Lk. 7,23, MT 11,6

[34] Joh. 20,29

[35] 1 Mos. 17,9-14

[36] 3 Mos. 15,29

[37] 2 Chr. 29,17

[38] 1 Sam. 16, 23

[39] Glarean, Dodekachordon, 1547, I Book XVI Chapter, 1988, 80

[40] In the papal index of Paul IV of 1599 we find “Henricus Glareanus Helveticus” under the “auctores quorum libri & scripta omnium prohibitur”, quoted from Kölbl, Autorität, 53

[41] Glarean, Dodekachordon, 1547, I Buch, XI Kapitel, 1988, 22

[42] Only the 8 can be integrated into the selected time frame of this study. Therefore, it should be pointed out at this point that the modern keyboard has 13 keys per octave with only 12 tone names, in analogy to the 13-1 symbolism of the Last Supper, see Belz, Polydisciplinary Considerations, 51

[43] Werckmeister, Musicalische Paradoxal-Discourse, 75 The author provides information on the far-reaching analogies to the Wheel of Fortuna, the Last Judgment, the Jacob's Ladder, the Heavenly Jerusalem and the number symbolism of the keyboard on www.aurelius-belz.ch and in Sakrale Handys, 2013

[44] The term "sound hole" is considered out of date in specialist circles, since from a physical point of view it is an opening for the equalization of pressure. The air flow can be shown with a tissue paper placed over it. Belz, Sakrale Handys, 37, gives a first parallel consideration of the tracery rose and the soundboard rosette

[45] The symbolism of the sound corpus goes back to Augustine and Hieronymus, see Wille, Musica Romana, 401

[46] Spinet of the Duchess of Urbino in the Metropolitan Museum, New York, on this see Belz, Sakrale Handys, 123

[47] Drawings of Henri Arnaut de Zwolle, Bibliothèque nationale de France, 128r, s. Belz, Sakrale Handys, 21, Rose od a Clavichord by Johann Heinrich Silbermann, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nürnberg

[48] Klavizitherium in possession of the Royal College of Music, London, see Belz, Sakrale Handys, 81ff

[49] Bader refers to this, Psalterspiel, 291 Hucke, Die Herkunft der Kirchentonarten, 258 even deduces the conclusion that the system of psalm tones and church modes does not come from Rome at all, but should be viewed as an achievement of the Carolingian Renaissance.

[50] Degering, Die Orgel, 60

[51] Against the background of the aforementioned imperial interest in sacred music, it is noteworthy that Paulus Diaconus was in Montecassino almost at the same time as Karlmann, brother of Pippin III, and was teaching at the court of Charlemagne.

[52] Aristotle pays special attention to the octave "... because, as it were, the sound seems to be the same, since the analogue of the sounds is perceived as equality, as the same as one", he writes in the XIX book of the Problemata Physica

[53] Baroffio, Com-porre e trasmettere le melodie liturgiche, 148

[54] Mk. 16,16: "Those who believe and are baptized will be saved, but those who do not believe will be condemned."

[55] e.g. with a fountain roof supported by 8 columns in the Godescalc Evangelistar, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Ms. nouv. acq. lat. 1203

[56] Mk. 16,1-7 Quacquarelli, L’Ogdogade Patristica, 59 particularly pointed out its importance in the ancient liturgy.

[57] Nicole Oresme, Livre du ciel et du monde, 1377, Paris BnF, Manuscrits, F 656, fo 69

[58] Guido von Arezzo, Micrologus, Kapitel XIII, 2

[59] Hermensdorff notes in his comment of his tradition of the Micrologus Guidonis,15: “The Γ was not, as has often been claimed, added to the system by Guido himself or in his honor, but rather before his time”.

[60] Riemann, Handbuch der Musikgeschichte, 246 pointed out that the harmonics were notated with octave strokes, which Wille, Musica Romana, 689 also draws attention to.

[61] Richter, Zur Lehre von den byzantinischen Tonarten, 215

[62] The author has already referred to this in RIMS 36, 2015, 57

[63] Joh. 8, 12

[64] Wille, Musica Romana, 104

[65] Richter, Zur Lehre von den byzantinischen Tonarten, 365

[66] The consonance of the prim is generated by its definition, for every phenomenon is identical to itself. The following is the definition at Wikipedia: “The pure prime is the interval between two identical tones. There is no gap between them, so the pure prime corresponds to 0 cents. "

[67] Kues, De docta ignoratia, XI

[68] Mail from Mons. Carlos Moreira Azevedo, delegate of the Pontificio Consiglio della Cultura from July 16th 2015 to the author

[69] Wyschnegradsky, Libération, 2013

[70] Further information on the figure eight of the affects, the figure eight of the vowels in the Germanic choral dialect and the connection between the 8 church tones and the colors are given by Bader, Psalterspiel, 292. In addition, reference is made to the studies by Straub 2009 and 2012 on the cloisters by Moissac and Monreale, in which connections between the sequence of column capitals and church chants were shown. Similar parallels between architecture and the step sequence of church modes came to light on the occasion of the measurement of the cathedral of Sessa Aurunca, Belz, Polydisciplinary Considerations, 70

[71] Kuhn, Koptische Liturgische Melodien, drew particular attention to this desideratum

[72] Belz deals with differently thinking in one's own cortex using the example of the encounter between religion and science, Sakrale Handys, 221

Literature

Aristoteles, Problemata Physica, übers. von Hellmut Flashar, Berlin, Akademie-Verlag 1983

Aurelius Augustinus, De musica libri sex, übersetzt von Carl Johann Perl, Paderborn, Schöningh 1962

Günther Bader, Psalterspiel, Skizze einer Theologie des Psalters, Tübingen, Mohr-Siebeck 2009

Giacomo Baroffio, Com-porre e trasmettere le melodie liturgiche: una retrospettiva verso il futuro, Rivista Internazionale di Musica Sacra 38, Libreria Musicale Italiana 2017, 57-156.

Aurelius Belz, Das Instrument der Dame. Bemalte Kielklaviere aus drei Jahrhunderten, Dissertation, Bamberg 1998.

Aurelius Belz, Sakrale Handys, Die Verwendung des Keyboards im Spätmittelalter, Hägglingen, Belz-Verlag 2013.

Aurelius Belz, Polydisziplinäre Betrachtungen zur Symbolik des abendländischen Tonsystems. Über die akademische Missachtung europäischen Kulturerbes, Rivista Internazionale di Musica Sacra 36, Libreria Musicale Italiana 2015, 49-79.

Boetius, Fünf Bücher über die Musik, übersetzt von Oscar Paul, Hildesheim - New York, G. Olms 1973.

Walter Burkert, Weisheit und Wissenschaft, Studien zu Pythagoras, Philolaos und Platon, Nürnberg, F. Steiner 1962.

Oliver Busch, Logos syntheseos. Die euklidische Sectio canonis, Aristoxenos und die Rolle der Mathematik in der antiken Musiktheorie, Hildesheim - Zürich - New York, Olms 2004.

Hermann Degering, Die Orgel, ihre Erfindung und ihre Geschichte bis zur Karolingerzeit, F.Steiner 1989 (Bibliotheca organologica 64).

Gregor von Nyssa: Acht Homilien über die acht Seligkeiten, aus dem Griechischen übersetzt, München Kösel 1927 (Bibliothek der Kirchenväter, 1. Reihe, 56).

Guido von Arezzo, Micrologus Guidonis de disciplina artis musicae, d. i. kurze Abhandlung Guido’s über die Regeln der musikalischen Kunst, übers. von Michael Hermensdorff, Trier, J.B.Grach 1876

Werner Heinz [Hg.], Kleine Kulturgeschichte der Achtzahl, Berlin, Monsenstein und Vannerdat 2016

Helmut Hucke, Die Herkunft der Kirchentonarten und die fränkische Überlieferung des Gregorianischen Gesanges, Gesellschaft für Musikforschung. Bericht über den Internationalen Musikwissenschaftlichen Kongress, Berlin 1974, Kassel, Bärenreiter 1980, 257-260

Nikolais Von Cues, De docta ignorantia, Ernst Hoffmann, Raymond Klibansky, Hamburg, Meiner 2014

Bernhard A. Kölbl, Autorität und Autorschaft, Heinrich Glarean als Vermittler seiner Musiktheorie, Wiesbaden, Reichert Verlag 2012

Magdalena Kuhn, Koptische Liturgische Melodien. Die Relation zwischen Text und Musik in der koptischen Psalmodia, Leuven, Paris u.a., Peeters 2011

Flora R. Levin, The manual of harmonics of Nicomachus the Pythagorean, Grand Rapids, Mich., Phanes Press 2001

Annemarie Jeanette Neubecker, Altgriechische Musik. Eine Einführung, Darmstadt, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft 1977

Adolf Nowak, Prinzipien und Modelle musikalischen Denkens in ihren geschichtlichen Kontexten, Hildesheim, Olms 2015

Christian Petersen, Naturwissenschaften im Fokus II, Grundlagen der Mechanik einschliesslich solarer Astronomie und Thermodynamik, Wiesbaden, Springer Vieweg 2017

Claudius Ptolemäus, Tetrabiblos, 3 Bücher über Harmonik, Nach der von Philipp Melanchthon besorgten Ausgabe aus dem Jahre 1553 übers. von Erich M. Winkel, Tübingen, Chiron-Verlag 2012

Antonio Quacquarelli, L’Ogdogade Patristica e suoi Riflessi nella liturgia e nei monumenti, Bari, Adriatica Editrice 1973

Ludwig Richter, Zur Lehre von den byzantinischen Tonarten, Jahrbuch des Staatlichen Instituts für Musikforschung Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Bärenreiter 1996, 211-260 und 1997, 325-390

Hugo Riemann, Handbuch der Musikgeschichte, Bd. I, Leipzig, Breitkopf und Härtel 1919

Rainer Straub, Die singenden Steine von Monreale, Salzburg, A. Pustet 2012

Rainer Straub, Die singenden Steine von Moissac, Salzburg, A. Pustet 2009

Eddie Vetter: Musik I (Musiktheorie), Reallexikon für Antike und Christentum, Band 25, Stuttgart, A. Hiersemann 2013, Sp. 220–247

Vitruv, De architectura libri decem, übersetzt von Kurt Fensterbusch, Darmstadt, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft 1981

Andreas Werckmeister, Musicalische Paradoxal-Discourse, Hildesheim, New York, G. Olms 1970

Günther Wille, Musica Romana, Die Bedeutung der Musik im Leben der Römer, Amsterdam, P. Schippers 1967

Ivan Wyschnegradsky, La loi de la pansonorité, mit einem Vorwort von Pascale Criton, Genf, Ed. Contrechamps 1996

Ivan Wyschnegradsky, Libération du son: Écrits 1916-1979, Pascale Criton [Anm.], Michèle Kahn [Übers.], Lyon, Symétrie 2013